It’s been a busy week for El Niño updates and information. On Monday, NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center (CPC) issued their weekly presentation (pdf). On Tuesday, the Australian Bureau of Meteorology issued their bi-weekly update. On Thursday, the CPC published their monthly discussion. And Saturday, Dr. Michael Ventrice wrote a guest post on Wunderblog.*

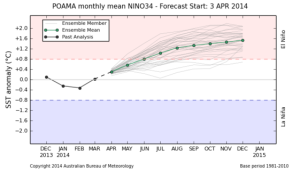

In short, an El Niño event is slightly more likely this summer (70% chance vs. 65%) or fall/winter (80% chance). The models currently predict a moderate strength event (+1.0°C to +1.4°C), but Dr. Ventrice is expecting the higher end at +1.5°C. For comparison, the lower limit of an El Niño event is +0.5°C and the “Super” El Niño of 1997-8 was +2.5°C. But, everyone put lots of caveats on these modeled results as estimating the strength of an event is much more difficult than the likelihood of one.

Regardless, Dr. Ventrice emphasizes, “Regardless of what amplitude the ENSO 3.4 Index [ed. El Niño strength] achieves, it only matters if the atmosphere responds.” (Emphasis in original.) His point is that while the Pacific Ocean is highly likely show El Niño-like temperatures, the impact on North America and the Atlantic hurricane season may not appear until August or later. That means there could be heat waves in the central and eastern continental US, continued drought in California, or regular Atlantic hurricanes until the atmosphere “feels” the effects.

* I recommend the Australian website as the easiest to read and understand. CPC’s updates are also good, but can take a few weeks or months to get the hang of the lingo. Dr. Ventrice’s posts are probably the most technical, but also provide excellent coverage into how an El Niño develops and what to watch for in the data.